We’re lucky to have NICE guidelines in the UK. A couple of years ago, on a visit to the US, one of my collaborators from the US mentioned how jealous he was that we have them. His practice was to get a CT scan for everyone with a head injury. The NICE guidelines give us a framework for implementing evidence-based decision rules like the Canadian CT head and CHALICE rules on a widespread basis. One area I think the NICE guideline for head injury can improve, however, is for anticoagulated patients with minor head injury.

The NICE guideline suggests that we scan head injured anticoagulated patients who have lost consciousness or have amnesia. In the absence of other high risk features, however, the remainder of patients are potentially eligible for immediate discharge without even so much as an INR check. This makes me worry.

Unfortunately, the Canadian CT head rule can’t really help us out here because that study excluded patients with coagulopathy. The New Orleans rule didn’t exclude coagulopathic patients but their analysis was, shall we say, somewhat underpowered as they only had 1 patient with coagulopathy in the study! So what is the evidence behind managing head injury in anticoagulated patients?

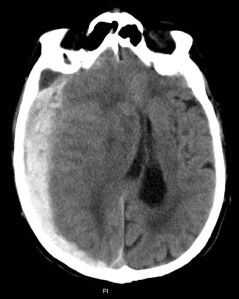

Fortunately, we do have some evidence, although it’s relatively limited evidence if we’re honest. A case series of 144 patients demonstrated that the incidence of clinically important intracranial injury in warfarinised patients was 7%. For me, that’s a sufficient risk to prevent me from ruling out a bleed in this group and to make me want to request a CT brain. Roughly 7% of patients with chest pain who have a normal ECG are having an acute myocardial infarction. But I wouldn’t dream of ruling out AMI just because the ECG is normal. So neither should we consider ruling out intracranial haemorrhage at that level of risk.

What’s more, anticoagulated patients who develop an intracranial haemorrhage may not meet the NICE criteria for CT (which are based on the Canadian CT head rule, incidentally). This means that they can bleed despite being relatively asymptomatic. And a subtherapeutic INR doesn’t mean we can relax either, as shown in this great study from John Batchelor and Simon Rendell from my own institution.

OK, so we’re going to get a CT for these patients. I’ve sold you that, right? But if the CT’s normal, surely we can relax. Right?

This great small study from Annals of Emergency Medicine sheds some light on that situation. The authors implemented a protocol to immediately CT all warfarinised head injured patients, observe them for 24 hours, then re-scan them. Of 97 patients, 87 agreed to stay in for observation and have a repeat scan. 5 (6%) of those patients had a late bleed, not detected on the initial scan. OK, it was minimal in 2 patients. But 1 required craniotomy. What’s more, only 1 of those 5 patients had showed signs of neurological deterioration in the 24 hour period between scans. 2 further patients developed late bleeds even after a normal scan at 24 hours. So, this study definitely tells us that there’s an important incidence of late bleeding in anticoagulated patients. Not only do we need to strongly consider scanning these patients, but we also need to consider repeating the scan 24 hours later, even in the absence of neurological deterioration. What’s more, the symptoms reported by the patient may not be a great predictor of intracranial bleeding. Only 1 of the 6 who bled reported a severe headache, and only 1 was vomiting. If we rely on our patient becoming symptomatic during the period of observation, we may still miss some late bleeds.

Of course, this is just one study. Other studies do confirm that there’s an incidence of late bleeding in anticoagulated patients, although it may not be quite as high as 6%. However, what’s clear is that these patients ooze, and they ooze slowly. Of course, we don’t want to miss a bleed, if present, initially. Given the prevalence of bleeding at the time of presentation, I suggest that we should still scan these patients at presentation. But we should also be alert to the possibility of late bleeds.

From discussions on Twitter, I know that people are doing this after 6 hours rather than 24. There’s no evidence to definitively tell us which strategy is better. In my practice, I’ll be strongly considering an initial scan, an INR scan, a period of observation and a repeat scan after 24 hours. It’s not clear whether that’s the optimal strategy. What is clear is that we must be extremely careful with these patients. They bleed. And they bleed late.

So, what about reversal of the anticoagulation? Well, that’s a whole different debate – you’ll have to watch this space!…

Rick Body